The country offers significant potential for attracting international visitors with stunning desert landscapes, mountain ranges, and archeological sites that would be flooded with tourists if they were elsewhere. But even Tripoli, the capital, is a pleasant city with a perfect balance of old and modern. The Italian colonial era left a lasting impact on Libya with several Italian restaurants, cafés, and shops. Events in 2011 ended the era of Gaddafi after 42 years, but the country drifted into a civil war. Since then, it has been identified with destruction and completely forgotten as a travel destination. The country is not free of tension even now, but the relative stability allows tourists to travel around the country, though with specific rules. The recent introduction of e-visa makes it a lot easier to get into the country. This travel guide helps you get an idea about what you can visit in Libya. You will be surprised at how unique this country is!

Most travelers visit Western Libya, and only a few head to the Eastern part, though it also has a lot to offer, from the Green Mountains to Cyrene, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. This is not for safety reasons but because anybody entering East Libya must pay a high tax. However, this may change in the future.

All you need to know about traveling to Libya (2025)

Tripoli, the capital

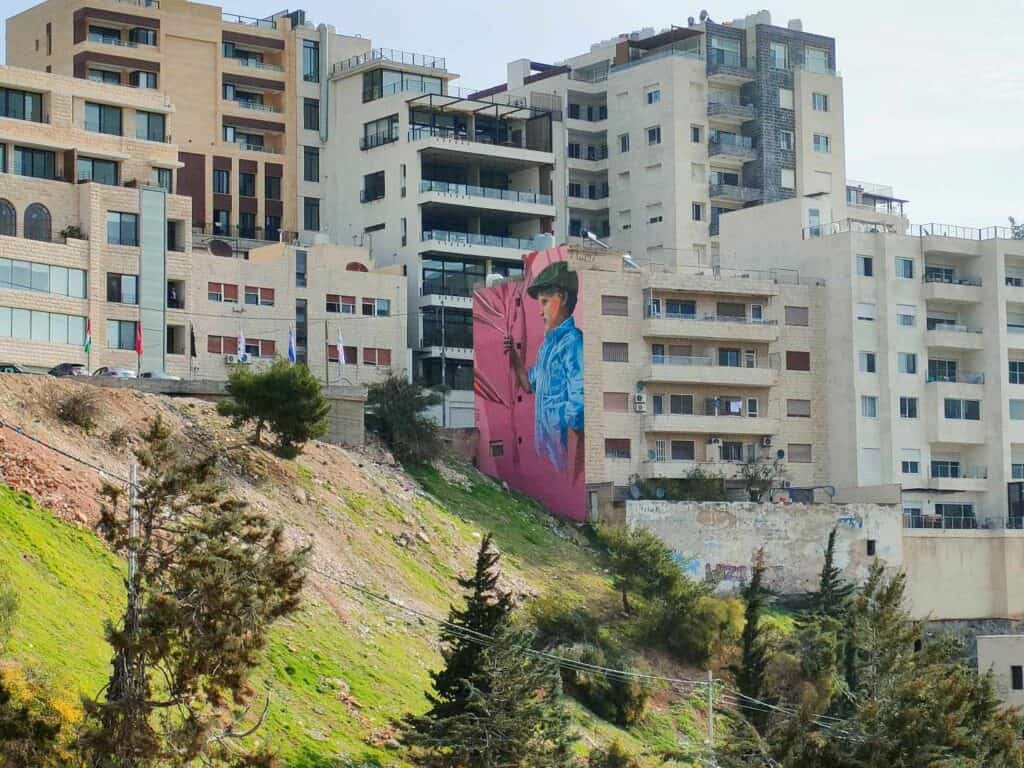

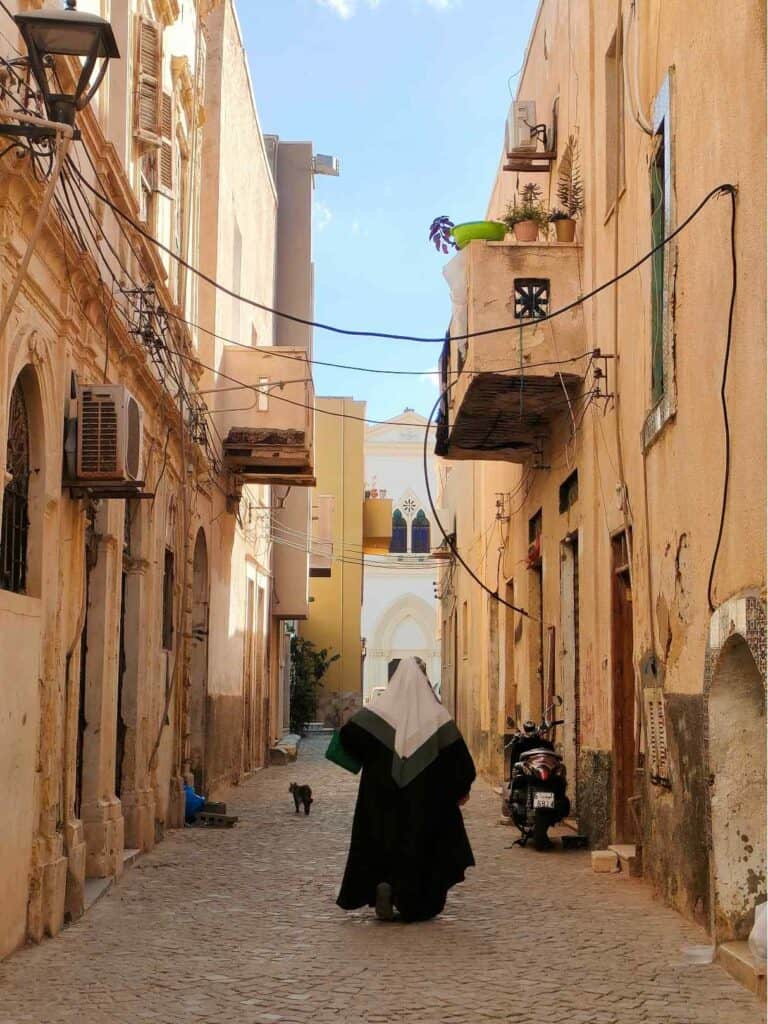

From the first minute, Tripoli made a very good impression on me. It looked much cleaner, greener, and livable than Tunis. Tripoli is a fine balance of ancient and modern. After wandering around in the maze of alleys of the old city, you can have a nice meal or café in a stylish restaurant along the seaside. The ongoing construction anticipates that Tripoli will be even more pleasant soon. For example, the entire Green Square was closed, the main meeting point for locals and the center of the revolution. It will be adorned with parks, fountains, and a nice place for families to walk around. The Green Square was renamed Martyr’s Square immediately after the revolution of 2011. At the same time, the construction of many buildings has stopped since the revolution, and the cranes have stood unmoved for over 10 years.

The Phoenicians founded Tripoli in the 7th century BC, and then it was in the hands of the Greek rulers of Cyrenaica as Oea. It is also called “Tripoli of the West” to distinguish it from the second-biggest city in Lebanon of the same name. Tripoli’s name derives from the ancient Greek Tripolis, which refers to Oea, Sabratha, and Leptis Magna, three main cities along the Mediterranean coast. From Oea, it was renamed Tripoli and was part of the region of Tripolitana. In the 2nd century, the Romans included it in their province, Africa. (This province later lent its name to the whole continent).

Out of the three, only Tripoli was not buried under the sand. However, with its expansion as a city, most of the Roman ruins were used as building material, and they built houses and streets on top of that. Thus, apart from Roman and Byzantine columns popping up in the old city and in some older mosques, the arch of Marcus Aurelius, built in 163 AD, is Tripoli’s only significant ancient site. It stands at the intersection of the Cardo and Decumanus and, therefore, marks the exact center of the Roman city. Oea had a single triumphal arch, while Leptis Magna had five, and Sabratha had none.

The best thing is to walk through the narrow alleys of the old city, with its shabby buildings, nice portals, and the bazaar where you can look at things in peace and nobody wants to cheat you. The most common things on sale were carpets, pottery, textiles, and regular souvenirs. One shop even sells bank notes from Gaddafi’s time. The souks (bazaars) in the medina (the old city) played an important role in the commerce between the trans-Sahara trading routes and southern European merchant ships.

Some of the attractions of the old town are the historical building of the former British Consulate, the Karamanli House, the 19th-century Ottoman Clock Tower (under renovation), the Banco di Roma building, and the Red Castle.

The city’s most famous landmark, the Red Castle, dates back to Phoenician times and was later painted red after the Spanish invasions in 1510. This is from where Gaddafi gave public speeches to the crowds on Green Square (today’s Martyr’s Square). The castle incorporates a museum with invaluable Libyan artifacts but has not been reopened since 2011.

The Bank of Rome (Banco di Roma) was the main vehicle of Italian emigration, managing land purchases, trade investments, and opening branches. It sponsored factories and mills and controlled maritime transportation between Italy and Libya in most major Libyan cities and towns.

Italian district

Tripoli underwent a huge architectural and urbanistic improvement under Italian rule. The first thing the Italians did was to create in the early 1920s a sewage system (that until then it lacked) and a modern hospital. Furthermore, in 1927, the Italians founded the Tripoli International Fair to promote Tripoli’s economy. They also organized the Tripoli Grand Prix, an international motor racing.

After the old city, discover the modern district, which has arcaded Italian-style buildings, Italian cafés, and Italian shops. Italian food is as common as traditional couscous, which includes meat or fish. Who would have thought you might eat one of the best pizzas in your life in Libya?! Here stands the former royal palace used by King Idris (1951-1969) after gaining independence.

The Jamal Abdul Nasser Mosque, the biggest in Tripoli, also stands in the Italian district. It was first constructed as a cathedral in the 1920s during the Italian Libya colonial era and converted into a mosque in the 1970s under Gaddafi’s instructions.

The Martyrs’ Square is the main meeting place for locals and is also the venue from where national celebrations are held. During the civil war rebels took control of the square and changed its name from Green Square (referring to Gaddafi’s color) to Martyrs’ square.

At the end of the day, head to the prominent district along the seaside with several nice shops, the Magnum sweet shop, and seaside restaurants.

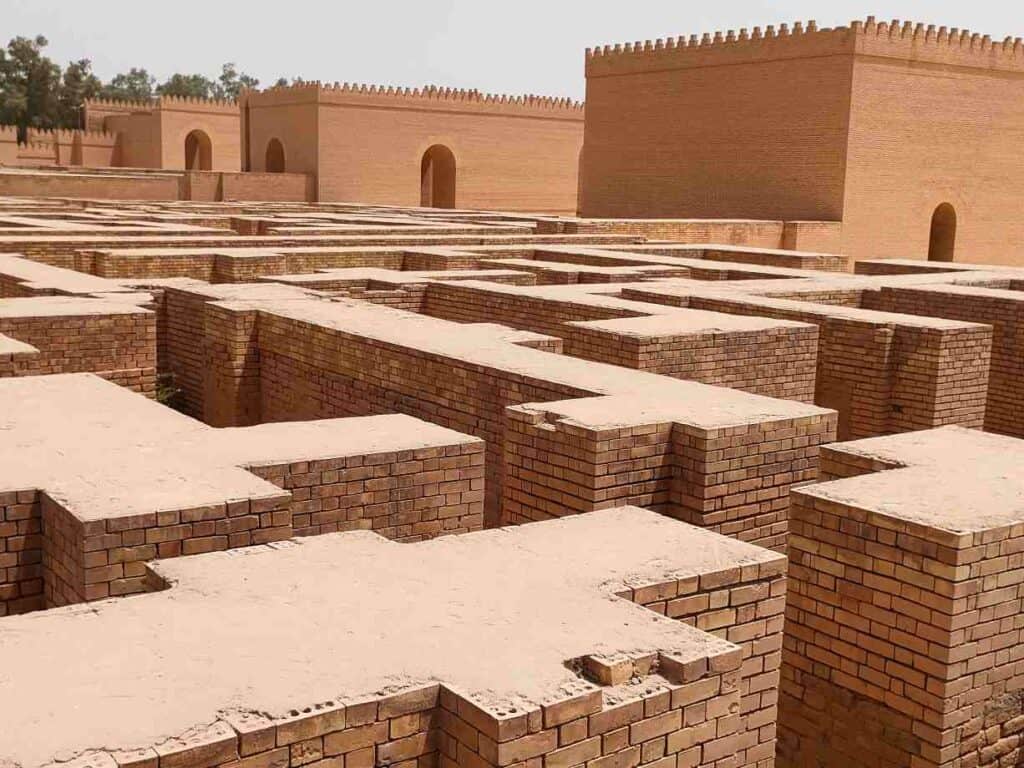

Leptis Magna (UNESCO), the highlight of the visit to Libya

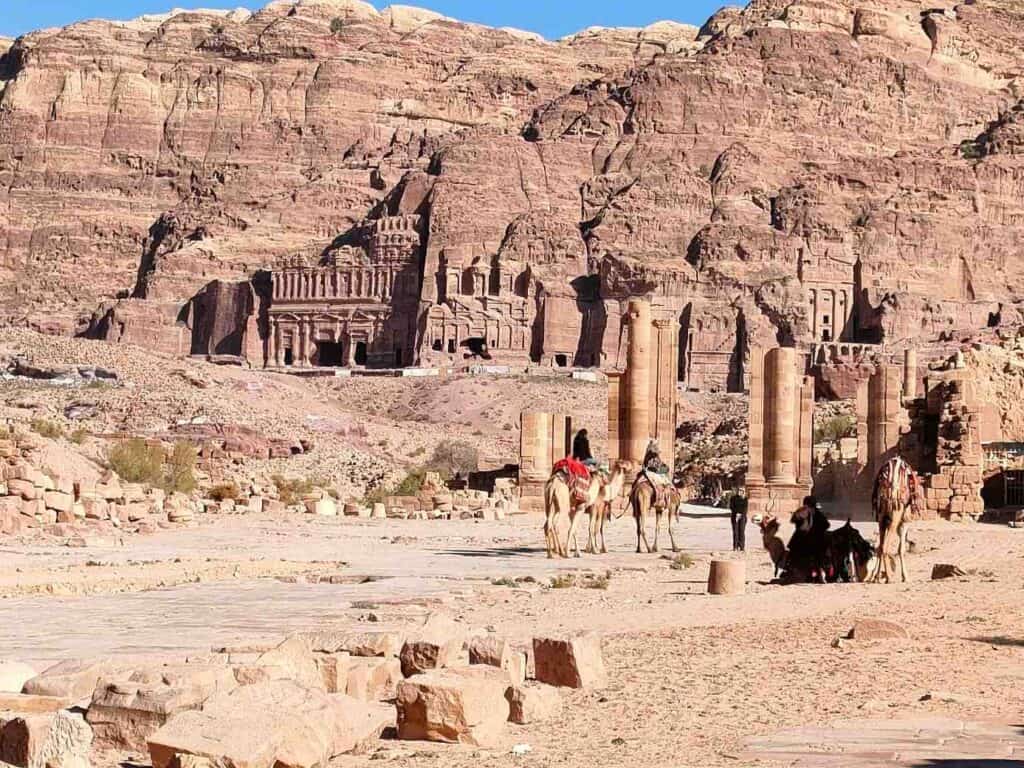

I never imagined finding such well-preserved Roman ruins in Libya, where, despite the bad weather, we spent close to 3 hours roaming around.

Phoenician merchants from the eastern Mediterranean recognized the commercial potential of Sabratha. They established regular ports along the Tripolitanian coast, where the primitive tribes from the southern Fezzan region sent caravans loaded with precious and fascinating items of trade up to the coast. Among these was Leptis Magna, which, like its sister establishments of Oea and Sabratha to the west, probably owed its early growth to these trans-Saharan caravans. The cultivation of olive trees was so successful that Leptis Magna became one of Africa’s largest centers for olive oil production. The area around Leptis Magna was an important wheat-producing region. Thus, Leptis Magna’s prosperity depended more on the agricultural produce of its inland holdings than on any caravan trade across the Sahara.

During the reign of Augustus, the increase in wealth and population demanded a change in the town’s physical appearance. They built forums, baths, temples (Bacchus and Hercules were worshiped as the patron deities of Leptis Magna), a basilica, a market, a residential building, and a port.

The Theatre is one of the most impressive parts of Leptis Magna. It was designed in the standard semicircular form used by the Romans, the orchestra and the lower rows of the seating area of the auditorium were excavated from the virgin rock of the site. A semicircular colonnaded walk ran around the upper edge of the supporting wall. In the middle of this colonnade, opposite the center of the stage, was set a small Temple of Ceres (among others, the goddess of what and motherly love).

During Emperor Trajan, it was raised to the rank of a Roman colony, and its inhabitants were considered Roman citizens with most of the attendant privileges. The great soldier-emperor Trajan was succeeded on the throne in 117 by one of the most interesting of ancient personalities, Hadrian. After overcoming the immediate problems of his succession and reviewing many of the provinces in the first of his great tours, Hadrian finally embarked for Africa in 128 A.D. This was only one phase of his overall project of visiting his Empire as much as possible to see existing conditions firsthand.

The earliest structures were created of fine grey limestone from the local quarries, but for the first time in the Roman history of Tripolitania, in the second century, marble became the main structural and ornamental material, changing the characteristic of Leptis Magna.

At the turn of the second and third centuries, Leptis Magna entered its last and greatest period of affluence. In its heyday, the city was the second most important after Rome in the Empire, with around 100,000 inhabitants. Emperor Septimius Severus, born in Leptis Magna, ascended the imperial throne in 193 A.D and maintained a strong attachment to the African provinces and Leptis Magna. The emperor always spoke Latin with a heavy African accent. He was one of the last great emperors.

All you need to know about traveling to Libya (2025)

Septimius embarked upon his eastern campaigns against the Parthian kingdom. Immediately upon his victorious return to Rome in 202, commemorated by the erection of the arch dedicated to him in the Roman Forum, he made arrangements to visit his place of birth. He initiated a building program to make Leptis one of the most splendid cities in Roman Africa. The primary evidence of this new program is the imposing four-sided arch, dedicated to Septimius Severus and erected over the crossroads of the city’s two main streets, the Cardo and the Decumanus in 203 AD.

The popular entertainment of Roman times, the contests with gladiators and wild African animals, were scheduled in the amphitheater to the east of the city, which was also one of the largest circuses in the Roman world.

Apart from that, the Hadrian Baths complex, the largest outside Rome, the forum, the basilica, the market, and the nymphaeum are the other places you must see once you visit Leptis Magna.

But the magnificence of the new Leptis Magna had been obtained at the cost of stability. The town’s treasuries had been emptied.

During the Italian control over modern Tripolitana, the Italian government encouraged its archaeologists to devote attention to these symbols of Rome’s ancient past.

I have never seen such a well-preserved Roman city, and a large part of it is still unexcavated. It was an unbelievable place, which tourists would flood if it were elsewhere.

Sabratha (UNESCO)

Like Leptis Magna, it was originally a Phoenician trading center, dating perhaps to the seventh century B.C. Extensive mosaic decorations and the theater are the main attractions of the archeological site, which can accommodate 5000 people, and the Mediterranean coast lends it an exceptionally splendid backdrop. The design is reputed to be a replica of the palace in Rome built by Emperor Septimius Severus, a native son of Leptis Magna. The Roman theater of Sabratha is said to be one of the most striking Roman monuments in North Africa, dating to the late second century.

Nafusa mountains (Gharyan, Nalut, Qasr al-Haj)

The Nafusa Mountains surround Tripoli like a crescent moon from the Mediterranean coasts to the Tripolitanian plateau. Serpentines lead up to abandoned ancient remote villages sitting atop the cliffs, where you enjoy a spectacular view of canyons and escarpments and the place where the plateau meets the Jafara plain. It is the heartland of the Beber people in the Tripolitana region. However, as Gaddafi didn’t acknowledge the Berbers as a separate ethnicity, they could not speak Berber and had to hide their identity. During the revolution, it was a rebel stronghold amid the mainly Gaddafi-controlled western part of the country. With the fall of Gaddafi, they started to use the colorful Berber (Amazigh) flag again, speak their language and preserve their culture.

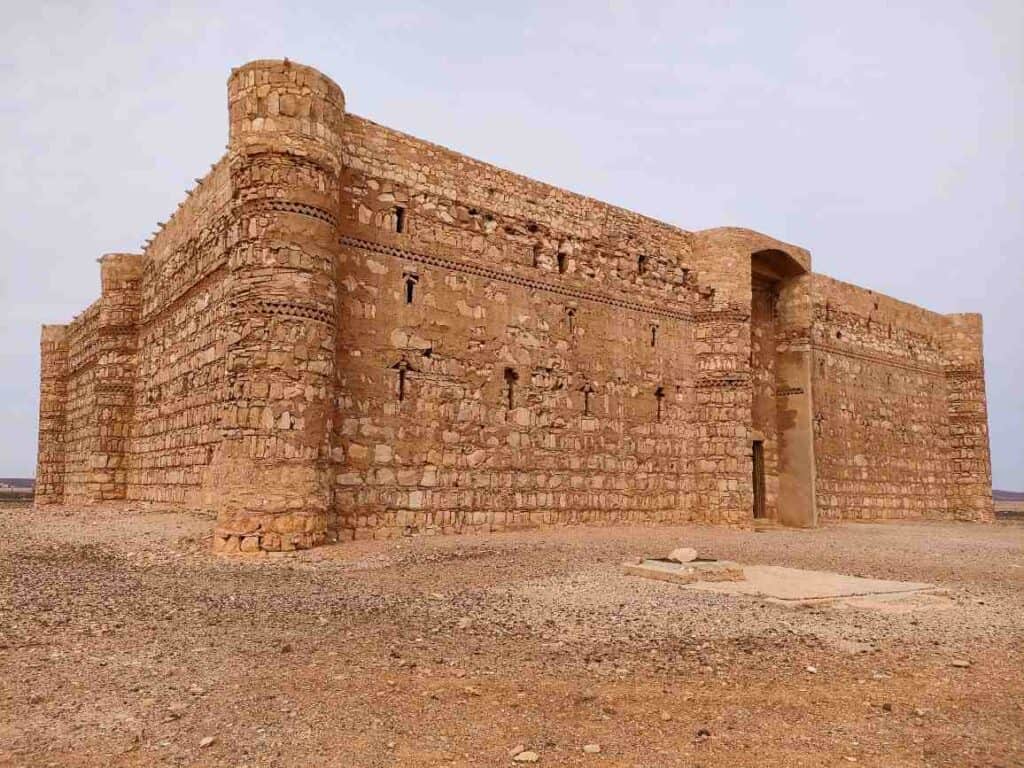

Like in Tunisia, you will see “ksars” (fortified granaries) in Libya as well, where Berbers used to store grains. Qasr al-Haj, dating to the 12th century, is a great example. The doors were made of palm trunks, which gave protection from insects and thieves. It was strictly regulated how much the owner could take when he needed it. Small flights of stairs connected the vaulted rooms (ghorfas) used to store grains. (a series of ghorfas form a multistory ksar). Another example of that is in Kabaw.

You can also have a stop in Gharyan, with the only surviving example of an underground house. Similar structures are found in the south of Tunisia as well, though the one in Libya is not touristic. These Berber houses are unique. They look like craters dug into the terrain some meters deep. The entrance is not seen at first because it leads through a tunnel from the side. The rooms surrounding the courtyard are small caves. Sometimes, more courtyards were connected.

What you should know before traveling to Tunisia + itinerary

Gharyan is also known for being a center of resistance against the Italian occupation. Today, the people of Gharyan live from oil production, carpet weaving, and pottery, which could be a great souvenir for you from Libya.

Nalut is another interesting city in the Nafusa mountains. It was an important stop for caravan trade, only 60 kilometers from the Tunisian border. It once had a monument dedicated to the Green Book of Muammar Gaddafi, but it was destroyed during the Libyan civil war. Walk around its old town and check out another fortified granary (ksar).

All you need to know about traveling to Libya (2025)

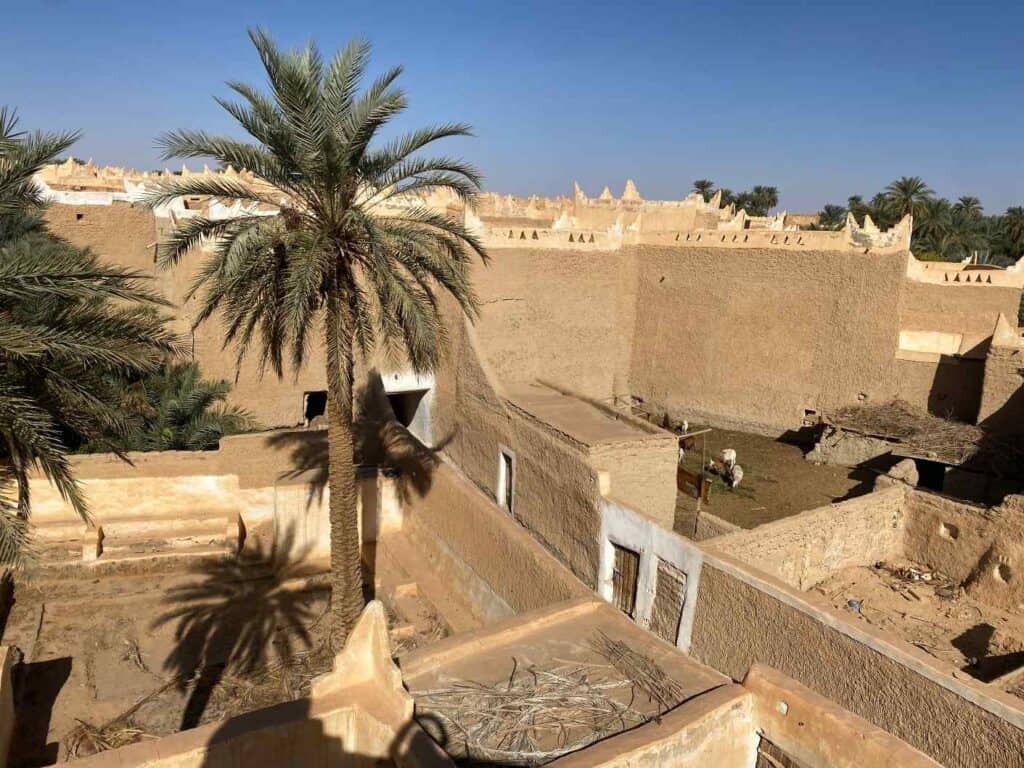

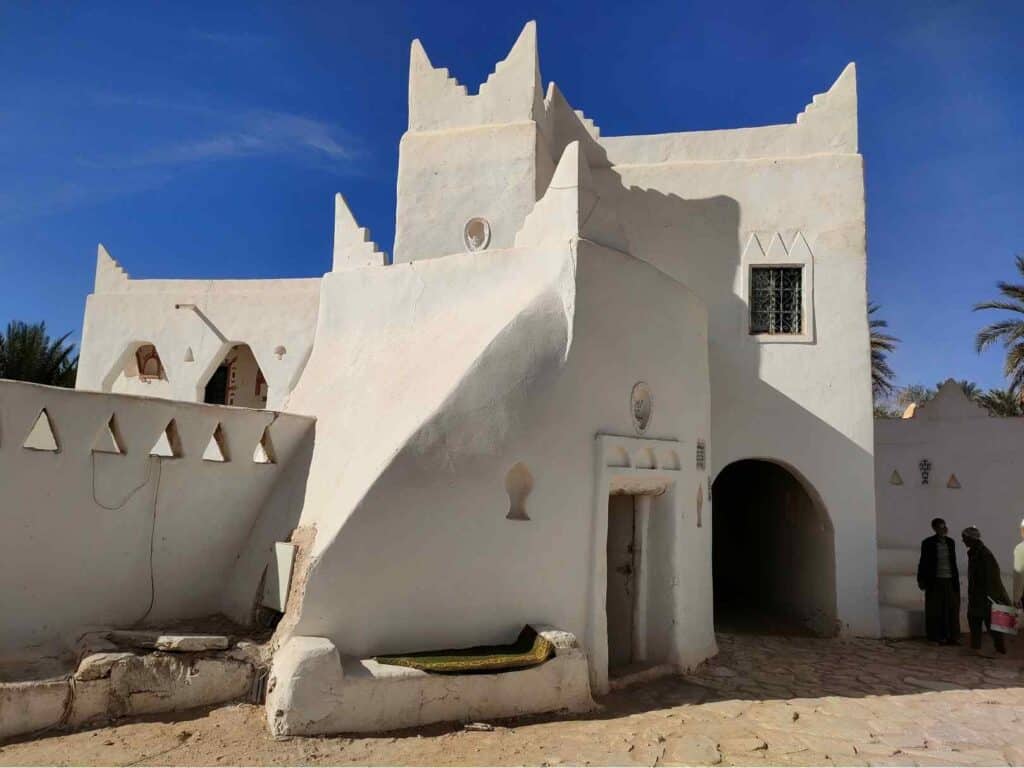

Ghadames, “the pearl of the desert” (UNESCO World Heritage)

Ghadames is one of the oldest oasis cities in the Sahara, and it was a center of trade between the sub-Saharan region and the Mediterranean, with a mainly Berber (Amazigh) population. Imagine when camels loaded with gold, ivory, and brass headed west to Timbuktu or the northern coast. Until the 19th century, slave markets were such an essential source of income for Ghadames that once it was abolished, Ghadames also started to decline. The French occupied Ghadames in 1943 and incorporated in the southern Fezzan region until the United Kingdom of Libya was proclaimed in 1951.

It is a long drive from Tripoli to Ghadames, located around 600 kilometers from Tripoli, close to the Tunisian and Algerian borders. Since the war, the land borders have been closed, but they may reopen soon. The road is long and deserted, crossing some villages and through the Nafusa mountains with some spectacular viewpoints. But don’t worry—it will be worth getting there!

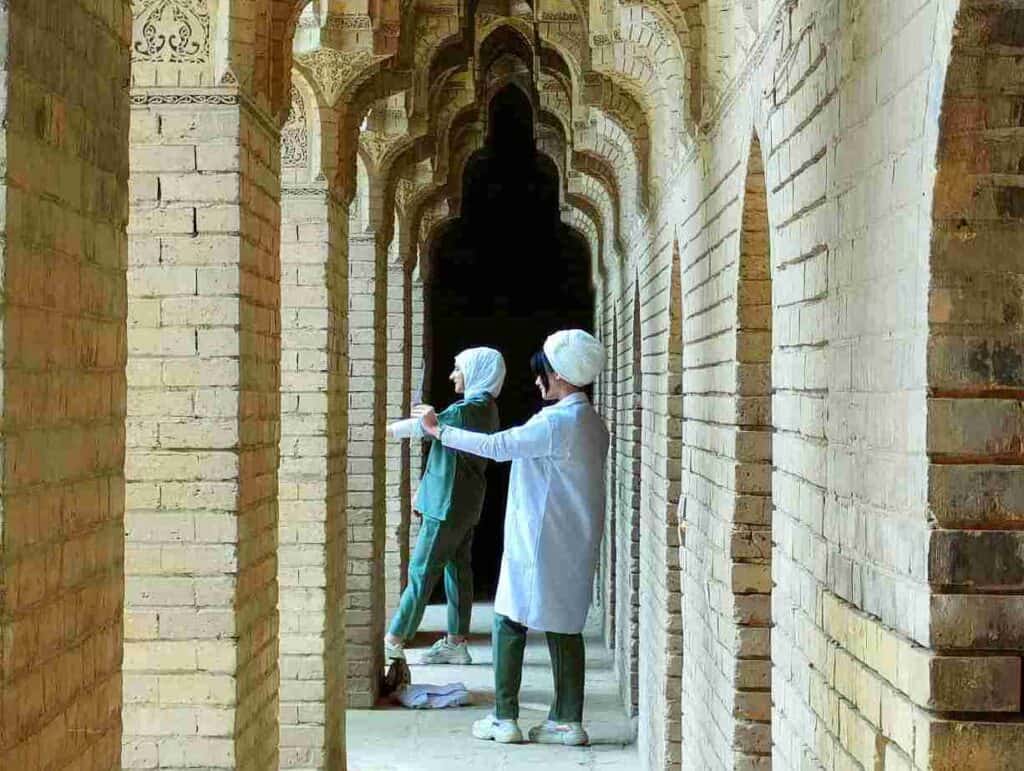

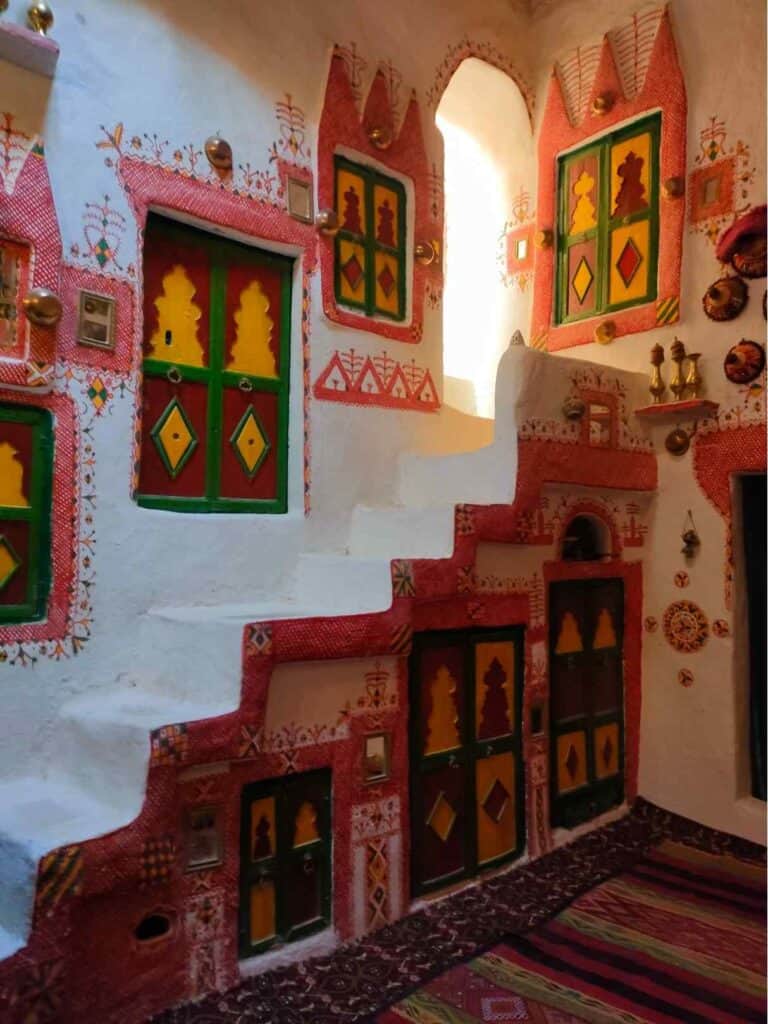

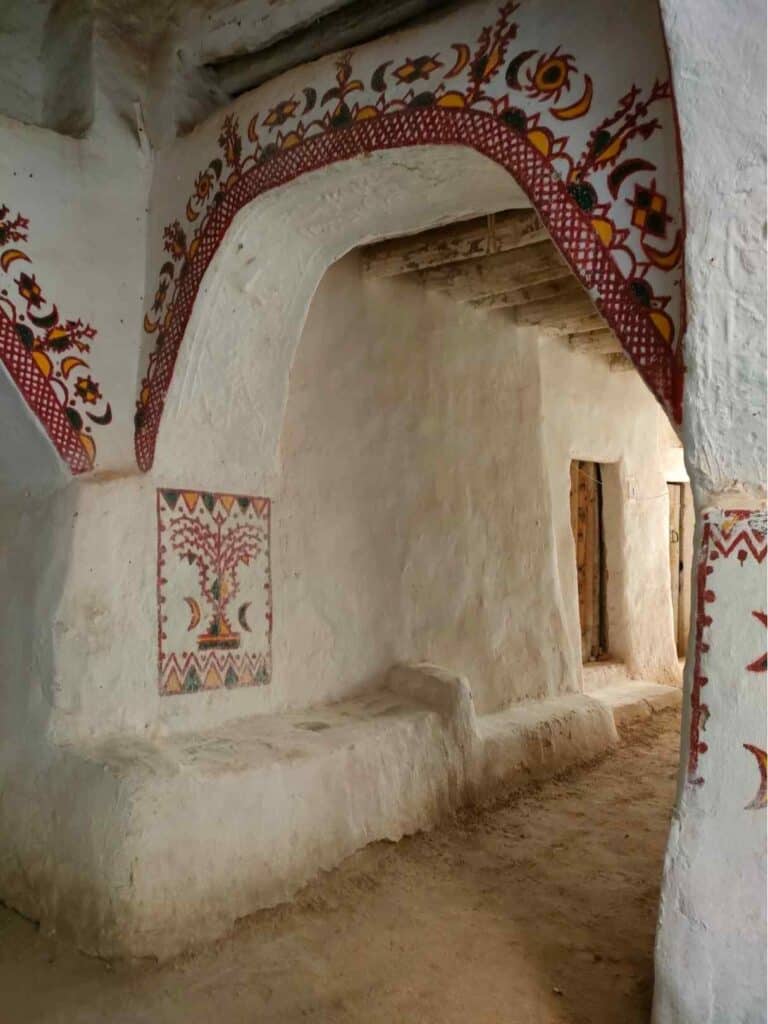

Ghadames has fascinating architecture that seems to be an underground city with a maze of covered alleys only occasionally opening up to let some light in and to help orientation. However, even if I returned a hundred times, I would still not find my way. The thick mudbrick houses built from the mix of mud, sand, and straw perfectly keep the interiors cool even when the outside temperature rarely exceeds 50 degrees during the hot summer months.

Life in Ghadames was arranged in layers: the underground area was storage, the middle section was the living area, and the rooftop was where women cooked, sewed, or socialized; some even slept there during the hot days. It also means they could enjoy the pleasant coolness of the “labyrinth city. You only see how each house is connected through narrow passages and steps when you climb the roof. This is where the bride and her female guests celebrated the weddings too. The pointed structures of the roofs are said to prevent djinn (malicious spirits) from landing on the roof.

The stunning white and ochre walls are interrupted by palm tree doors, sometimes decorated with unique patterns indicating that the house owner completed the hajj (the holy pilgrimage to Mecca) or colorful patterns, the hands of Fatimah, or other symbols that have probably some mystic meaning behind them.

However, due to the water shortage and lack of modern sanitation, Gaddafi built a new city besides the mudbrick city, where all the people shortly moved. There was only one woman who resisted, and finally, they let her die there. Everybody preferred living in the old part and keep on talking about it with nostalgia. In its heyday, this mudbrick town deep in the Sahara had 15,000 inhabitants. Even the British consulate occupied a brick house there.

The most important building in Ghadames is a former religious school, which is also featured on the 20 Libyan dinar banknote.Next to the old town, there was once a luxury hotel built in a similar style, where many celebrities, including Sophia Loren, stayed. (She was in Libya filming the movie “Legend of the Lost,” which also stars John Wayne.) The hotel is intact on the outside, but inside it is in ruins.

Don’t miss going on a desert tour in the late afternoon. During this time, you can climb to see both Algeria and Tunisia. Then, your experienced driver will drive up and down the golden dunes, from where you can enjoy the sunset. You can finish the day by having a cup of tea with the local Berbers, who even serve fresh bread baked in the desert.

Ubari lakes

The Ubari saltwater lakes in the Fezzan region have a unique location in the middle of the vast, arid desert. You can swim in the crystal-clear waters while being surrounded by sand dunes. The best is to combine the Ubari lakes with the Acacus Mountains, an area known for its prehistoric rock art. However, visiting these more remote places takes an extra 5-6 days. It is important to contact a local travel agency as it is in the territory of the Eastern government, and the rules to obtain a permit may change.

Misrata

You may also visit the thriving commercial city of Misrata in West Libya, the third largest city in Libya after Tripoli and Benghazi. Many successful business people come from Misrata. It has few tourist attractions, except a War Museum about the Libyan war of 2011. Apart from weapons, a US fighter plane, personal objects of Gaddafi are also on display (the Quran of the former Libyan leader, his chair with which they transported him after his capture to Misrata). Even his body was kept here for 5 days. The museum stands at the place of the most intensive fighting and was dedicated to an Al Jazeera cameraman who died in Benghazi while reporting about the war.

All you need to know about traveling to Libya (2025)

Benghazi

Historically, Benghazi was an important Greek and Roman city, and remnants of these periods are still visible. Apart from that, Arab, Ottoman, and Italian architecture display the city’s diverse history.

The Benghazi Lighthouse is a well-known symbol of the city, with stunning views over the Mediterranean. The El-Berka palace, built at the end of the 19th century, is the largest Ottoman monument.

The Qasr al-Manar Palace, the site of the first university in Libya and the former residence of King Idris in Benghazi has been severely damaged and is now under restoration. This important heritage site will be turned into a museum.

Cyrene and Apollonia

Greek colonists founded Apollonia, which became one of the major trade centers along the coast. Initially, it was closely linked to Cyrene as its harbor, but it developed into an independent city once the Romans arrived. Interestingly, the remains of the ancient city were discovered underwater. Because of that, the port of Apollonia, dating to the 6th—7th century BC, has been exceptionally well-preserved.

Apollonia also has a Greek theatre dating to the 3rd century BC and palaces and churches from the Byzantine period. Here stands the Temple of Zeus, which is larger than the Parthenon in Athens, and the Temple of Apollo, which dates back to the 7th century BC.

The Green Mountains

The Green Mountains, or Jebel Akhdar as the locals call them, are probably the most beautiful part of Libya. Few would imagine that such a lush, green mountainous landscape also belongs to Libya, a country that is mainly covered with desert. The mountain range is up to 900 meters and spreads over 300 km East of Benghazi. Little wonder, the densely forested region gets the most rainfall during the year in Libya.

Libya is unlike other Maghreb countries (Algeria, Tunisia, or Morocco). It will probably come as a surprise how much it has to offer, from several World Heritage sites to stunning desert and mountain landscapes. Leptis Magna is the most well-preserved archeological site I have ever seen, and it would be flooded with tourists if it were not in Libya. Tripoli is a pleasant city with a charming old part and nice restaurants; Ghadames, the oasis city, has its own charm with the covered alleys and mud brick houses. The Nafusa mountains, with villages built on cliffs, are home to the Berbers, and the Green Mountains are strikingly forested in contrast to the rest of the country. The Italian colonial past greatly impacted the country with Italian-styled buildings, restaurants, and cafes. Libya still hasn’t recovered from the events of the civil war that erupted in 2011, and there is constant tension in this highly fragmented country. However, since getting a tourist visa has become easier and the situation has improved a lot lately, it is possible to discover Libya again under certain conditions.